Amid the changing financial environment, associations will need a clear focus on quantifying and capping off downside risks, write Jonathan Clarke and Phil Jenkins of Centrus

If any observers of the social housing market thought that the job of the treasurer was an easy one – rolling into one’s home study at 10 am and watching swaps slowly unwind or nudging along some security preparation for next year’s capital markets issue – then apart from being grossly misinformed, they certainly ought not to be thinking that now.

The political and financial turmoil of the past couple of weeks have focused minds; S&P’s awarding on 30 September of a “negative outlook” to the UK’s (AA) rating is in our view a harbinger of negative ratings movements in the medium term. This new path can be navigated, but any hopes that post-COVID we were heading back to the financial world of, say, 2015 have by now been dashed.

The economic and financial markets are the most uncertain they’ve been since the financial crisis, with Credit Suisse’s chief executive being forced to defend the bank’s “strong liquidity position” over the weekend (1-2 October), as soaring credit default swaps suggested market concerns.

In that context, we thought it would be of interest to refresh a piece of analysis we did five or six years ago looking at sector profitability.

‘Innocent times’

A few years into the post-financial crisis period – in the middle of last decade – the macro-economic environment was working out pretty well for housing associations (HAs). Rates were held low and market participants were relaxed about the lack of long-term exit strategy from the various forms of government intervention that sustained that position.

Inflation was positive and low and generally flowing through to rents. Researching for this article, we were reminded of anguished debates over whether Consumer Price Index (CPI) plus one per cent was very slightly worse than Retail Price Index (RPI) plus 0.5 per cent and the ending of rent convergence. (Those were innocent times!)

The broader issues around the lack of affordable housing were very real, but the job of the HA financial risk manager left plenty of strategic space for thinking about development and investment.

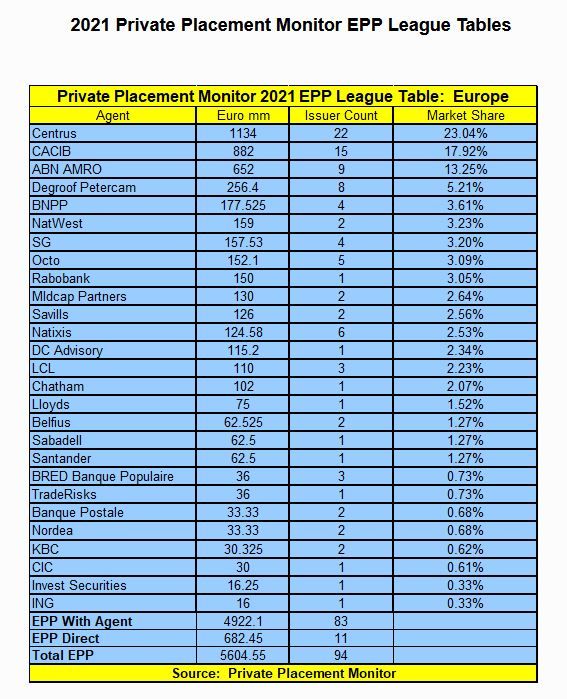

The chart above shows the global net surplus for the sector. Pre-financial crisis, the sector net surplus was just a few hundred million pounds. It’s a lot more now, having grown steadily between 2010 and 2018 and peaking at nearly £4bn in 2018, before dropping back to a little below £3bn in 2020 and 2021.

This reflects these macro factors and the growth in surpluses from sale. We’ve analysed what the net surplus would have been had rates been a more constant five per cent (see dotted line), roughly where the weighted average cost of debt (WAAC) was in, say, 2009, since when it has dropped by about one per cent overall. On that basis, the past couple of years would have been circa £2bn per annum, so still well above pre-financial crisis levels.

On one level, this is a reasonably encouraging picture of health. But focusing just on surplus underplays challenges around higher indebtedness and therefore riskier balance sheets, as well as the emerging investment requirements of existing homes (ie fire safety and decarbonisation spend), which feature in only a limited way in the historic data.

Also, of the circa £3bn FY21 net surplus, surplus from all types of sale was circa £1.5bn. Without that (relatively) risky activity the net surplus with normalised finance costs is not so different from where it was 15 years ago.

Debt per unit and rent policy

In terms of balance sheet profile, the chart below shows the path of indebtedness over the same time period.

Debt per unit growth has significantly outstripped CPI. The early years of this period saw an RPI link and the uplift of rent convergence, but we also have the more recent ‘minus one per cent’ years, and looking to the future the likely five per cent cap. More fundamentally, we are now in an environment where earnings and therefore market rents, to which social rents must in a loose sense be anchored, are not growing in real terms.

In a nutshell, pre-financial crisis the sector made little profit but took little risk. For the past 15 years it has taken risks but been rewarded with much higher profitability, and most forays into development for sale have been successful. But profitability is now back under pressure and cash is being diverted to non-remunerative investments in fire safety and decarbonisation.

Even if these investment concerns are overstated (many associations do not have material fire safety issues, in particular), the underlying model in terms of letting the balance sheet take the strain is in a different place to where it was at the start of this period.

What does it all mean for HA finances?

We draw a couple of key conclusions for HAs’ finances. First, interest rates (and perhaps volatility) are likely to remain at elevated levels compared to the past few years, and perhaps return to being more grounded in the underlying realities of how much private actors require as compensation for delayed consumption (eg meaningfully positive real rates).

Investment decisions will need to reflect this.

Second, while the need for more affordable housing and the investment requirements of existing stock are very real, HAs are at risk again of being seen as cash cows by government. And this is in the context of inflation pressures which may, if rent caps persist for any length of time, create a material inflation mismatch between revenues and costs.

Other sectors and indeed actual people will be feeling the same (or greater) pressures. But if the risk profile of a business has changed, then the approach to corporate finance risk management changes too.

For much of the past decade, financing and hedging decisions for many of our clients have been a relatively relaxing exercise in choosing the best option out of a relatively wide range of acceptable and easily obtained alternatives.

What is needed now is a clear focus on quantifying and capping off downside risks in ‘technical’ areas such as interest rate hedging and access to financing (particularly for weaker credits), but also through ensuring that the financial management of the business as a whole is joined up. This extends to controls over the development programme, integrating financing and asset management decisions, and investing management time in high-quality processes around budget-setting and monitoring.

Jonathan Clarke and Phil Jenkins, Managing Directors, Centrus. Originally published in Social Housing Magazine, 2022

For more information, please contact phil.jenkins@centrusadvisors.com