Goodbye 2022

We wave goodbye to 2022 perhaps with more of a sigh of relief than a tinge of sadness. For it has been a difficult year in which hopes of a “return to normality” after the disruption of the COVID lockdowns were dashed by a confluence of events which have rocked households, businesses, economies and countries to their foundations and demonstrated the fragility of systems which operate without hitch for long periods of settled and benign conditions but which can break apart rapidly under stress.

Variously, 2022 brought us:

- War in Ukraine – arguably the first major strategic armed conflict in Europe since WW2. Aside from the obvious and terrible humanitarian toll being inflicted, the knock on effect in geopolitical and economic terms is still unfolding, but will likely be profound. The sanctions imposed by the US and its strategic partners in Europe have fractured the global energy supply system and perhaps signalled the beginning of the end for the dollar-based global monetary system.

- Leverage & fragility – in the second half of 2022 the UK experienced a financial convulsion on the back of the Truss/Kwarteng mini-budget. Exploding gilt yields led to a spiralling liquidity crisis for UK pension funds employing LDI investment strategies (basically leveraging assets to drive higher returns in a low interest rate environment) and ultimately forcing the Bank of England to capitulate and re-start its gilts purchase programme temporarily. While many viewed this as a UK specific issue, it was one of a number of rivets popping in an over-leveraged system with rapidly rising bond yields and a rising dollar. Other tell-tale signs were a massive provision of dollar liquidity to the Swiss Central Bank from the Fed, most likely to aid a well-known Swiss bank and the Japanese Central Bank being forced to ditch its 25bps peg on 10 year Japanese Govt bonds in order to prop up the Yen –a supposed safe haven currency whose value had dropped precipitously against the USD.

- Inflation at 40-year highs – the energy crisis and broader supply chain issues saw inflation rising to multi decade highs putting further strain on household, business and government finances with the cost of living feeding through to demands for wage increases and widespread industrial action by public sector workers.

- Interest rates – with Western Central Banks having long argued that growing inflationary signals were “transitory” in nature, they were forced to throw in the towel in 2022 and to spend much of the year playing catch up by increasing policy rates at an unprecedented pace with bond yields following a similar trajectory. It has become increasingly clear that Central Banks face the unenviable challenge of having to act to control inflation (politically a high priority), whilst minimising the impact on growth with many economies already heading towards a recession. The end of a 40-year bull market in interest rates and the end of an era of easy money experienced since the global financial crisis is likely to have profound effects on asset prices which were driven up by a combination of lower equity return requirements and cheap and easy debt; further impacting consumers sense of a reduction in wealth.

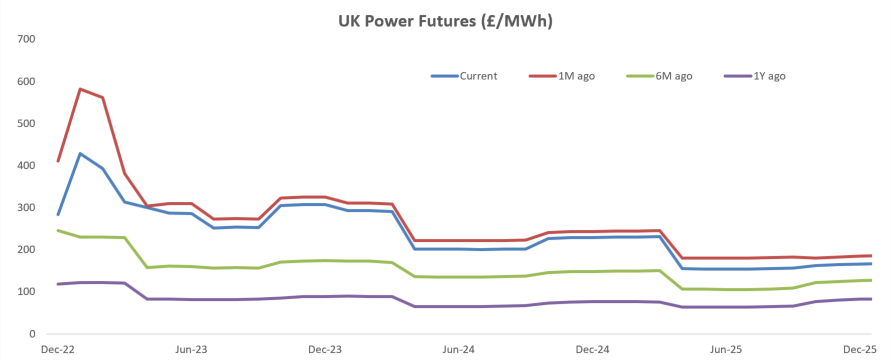

- Energy Crisis – UK and Europe (along with other net energy importers) saw dramatic spikes in energy costs, partly as a result of sanctioning one of its major suppliers of oil and natural gas but also in part as a result of poorly thought through energy policies going back many years, including lack of strategic energy security planning and over reliance on intermittent renewable energy without the necessary storage technology to cope with this. This has led to enormous pressure on households and an existential threat to energy intensive industries in the UK and EU. Governments with already high debt to GDP ratios were forced to step in with energy price cap mechanisms –putting further strain on public sector finances.

Each of these issues in isolation would be a serious and newsworthy event. The fact that they happened concurrently felt rather like living through one of those “perfect storm” scenarios that businesses use as an extreme but highly unlikely set of events designed to test a business plan to breaking point.

In the immortal words of D:Ream and New Labour, surely in 2023, Things Can Only Get Better? We certainly hope so. We found 2022 a tough year to do business and we know that many other businesses are far more exposed to the above issues than those of us working in professional services and finance. Rather like after COVID, we would though caution against any near-term expectations of a “return to normality”.

Sadly, there appear to be few signs of an end to the Russia-Ukraine conflict and with the major powers directly and indirectly involved seemingly entrenched, escalation at this stage seems a more likely eventuality than peace.

While the energy crisis will likely give a long-term boost to the UK and Europe in terms of energy security, supply, clean energy production and energy storage, for the time being, those countries and regions which are self-sufficient in energy resources will be far better placed to ride out the crisis than those reliant on imports. And with government finances being stretched further from an already highly leveraged position, financing of deficits in a world where the natural marginal buyers of government debt (think China, Russia, Middle East & Japan) may no longer have the same appetite for debt issued by Western nations, there may come a point where these countries face an unenviable choice of paying more to borrow, raising taxes or cutting their cloth to reduce deficits into slowing or recessionary conditions.

While many in the financial markets eagerly await the much vaunted “Fed pivot” – i.e. the point at which Chairman Jay Powell throws in the towel on interest rate increases and rides to the rescue of an ailing economy and stock market, he continues to surprise pundits with his clarity of purpose and clear determination to continue on his hawkish path until inflation is brought under control. Perhaps he will eventually pivot, but it may well only be once the Fed has seriously broken something or other be that Main Street, Wall Street or indeed set off a global financial crisis of some shape or form – that political pressure on the Fed might force a change of tack.

Our advice for 2023

So, our cheery advice for 2023 is to hope for the best but prepare for the worst and in doing so, we would recommend the following:

- Ensure that your business plans factor in the possibility of sustained and/or higher interest rates, sticky inflation and continued volatility.

- Leave higher than normal risk buffers in business plans and credit rating scenarios.

- Factor in higher than normal execution risk for any major financing, merger, acquisition or sale process and allow much longer for transactions to complete.

- Prepare well in advance and earlier than normal for funding processes and ensure you have fall back options in case of further bouts of market disruption as experienced in 2022 –strategic flexibility will remain key throughout 2023.

- Consider the impact of higher cost of debt and equity capital on asset prices – although this hasn’t been clear across all asset classes, it is reasonable to expect an on-going adjustment as buyers and sellers adjust to a new normal.

- Be aware of the higher propensity for political interventions as pressure increases on the government to assist under pressure households and businesses and control government finances.

- Assume energy costs remain elevated for longer with associated impacts on EBITDA, and plan the energy strategy and narrative around outperforming those assumptions.

As ever, the team at Centrus is here to support our clients in navigating these choppy waters. If you would like to contact a member of our team or want more information on any of the topics mentioned, please email london@centrusadvisors.com